“When the little negro girl recovered sufficiently from the injury to her brain to resume her tasks upon the plantation she was prone to strange dreams, which came to her suddenly while working or while conversing with fellow slaves.” Anonymous Journalist, San Francisco Chronicle, 1907

“You can put me in [the] paper feet up [and] head down, but don’t forget to put that in, too, for I sho’ belong to the G.A.R. (Grand Army of the Republic).” Harriet Tubman, as quoted by said journalist.

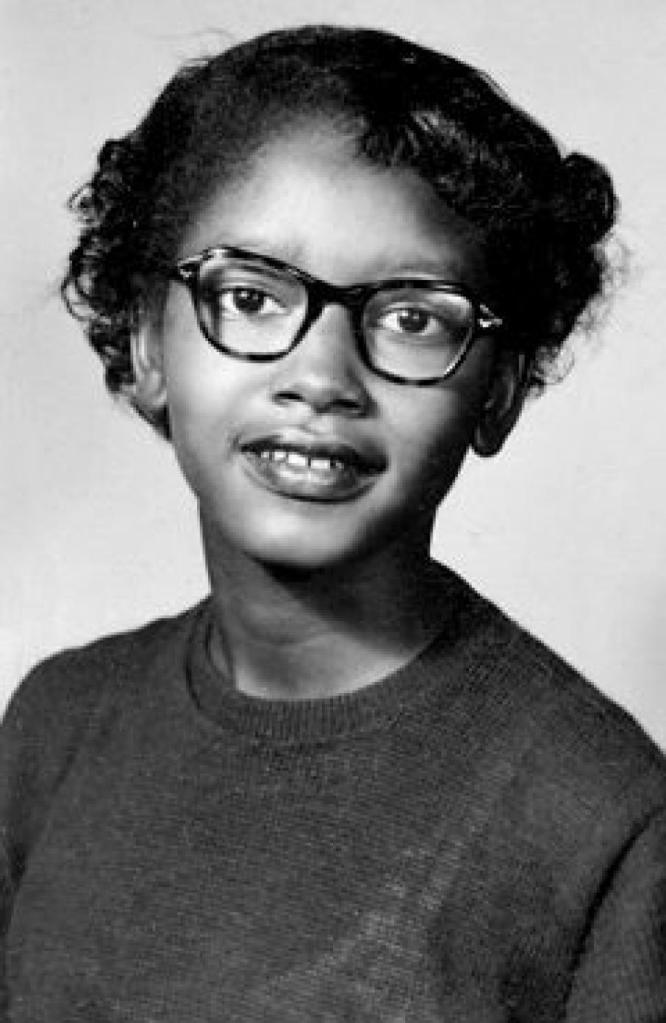

We owe Ms. Claudette more than an honorary degree, but that would be a start.

In the second place, she wasn’t pregnant when was arrested for trying to teach the police officers about the constitution. Her first son came months after this genius enactment of the pedagogy of emancipation, well after the people proved the adage that a prophet is only dishonored in her own home.

In the first place, we have to be more critical (I can hear my friend Diana saying ‘got to be mo careful’) of one-sentence stories. You know the type– the compound sentences that begin with x would have done y, but z happened because of a. In the case of Ms. Claudette, the compound sentence version is “Claudette Colvin refused to give up her seat months before Rosa Parks, but the NAACP decided not to rock with her because she was pregnant.” There’s hardly a story about Ms. Claudette that doesn’t frame this story as a clash between teenage pregnancy and middle class respectability. The truth is even more insidious (but also more thrilling).

First off. We don’t do firsts over here. We think time Blackly, as in on a continuum based on the work never being all the way done so you may’swell do away with the concept of organized time and be thankful that the sun rises as predictably as it sets. She wasn’t the first to refuse segregated busing; she was the only person in her city to refuse to plead guilty. By refusing to pay the fine that had thrown Black Montgomery citizens’ budgets for years, she bucked the system. She was fifteen. She thought she was a child. She thought the worst thing that could happen to her was juvenile detention. She thought it would be over soon.

By the time it was, the city had dropped the charges that were unconstitutional (I.e. refusing to move on a bus her parents’ tax dollars paid for) and saddled her with an assault on a police officer.

Things began to fall apart. This is why uplift narratives don’t work. She knew the road from sharecropping to civil rights attorney was a narrow one, but she preceded Toni Cade Bambara’s Hazel in saying, “Ain’t nobody gonna beat me at nothing.”

You can’t praise our risk-taking and make our mistakes so expensive. That’s not how this works. That’s not how any of this works.

This is what revolution cost Ms. Claudette: a scholarship. A pathway to continue to defend Black Montgomery residents against oppressive policies. It takes all kinds. Montgomery needed all hands on deck.

The NAACP has a class problem. Founded by W.E.B. DuBois as an imagined talented tenth, it attracts the kinds of people who have enough leisure time to think about the Negro problem and enough money to publish fliers about their thoughts. This isn’t to belittle the work of the NAACP: all hands on (different parts of the) deck.

But revolution, at base, is a radical change. And when a Black girl decides to behave as though the world is already as it should be, a revolution is at hand. Ms. Claudette was 15 and brilliant. 15 and a grade ahead of her peers. 15 and determined to study at Alabama State University and become a civil rights attorney. 15 and mourning her little sister. 15 and mourning the life of the cute boy who’d been falsely accused of raping a white girl. 15 and fed up. 15 and brave. 15 and mourning a little sister named Delphine who liked to sing and dance through the night, asking how to spell words. It was polio that took her. But it was also George Draper, the eugenicist who delayed Black folks’ medical treatment for the disease by alleging that it didn’t affect Black bodies the way it affected White ones. The integrated hospital that treated little Delphine when it was already too late had only opened the year prior. She was not 15 and pregnant.

Ms. Claudette was isolated when she met the man who would father her first child. I don’t want to lay her isolation at any one group’s feet, but there were lots of culprits who have since named themselves and been named by Ms. Claudette in the children’s book about her that was based on her interviews. When she met this grown-azz man, she’d already been marked a trouble maker, lost a scholarship, and been made fun of by her peers for going natural 60 years before corporations would corner the natural hair care market and make it acceptable for people with 4c hair not to straighten it before walking out the door. She was a mark. He was a predator whose name does not belong in the story of a brave girl who took the constitution literally.

There’s more to say but this is already too heavy so I’ll skip to the end until this finds a more permanent home…

Ms. Claudette, I just wanted to say thank you. For your wild ways. For your smart questions. For your pride in your lips, your skin, your hair. For sparking a revolution.

Do you like this section of my brain museum? If so, please consider stopping by the giftshop on your way out.

Make a one-time donation

Make a monthly donation

Make a yearly donation

Choose an amount

Or enter a custom amount

Your contribution is appreciated.

Your contribution is appreciated.

Your contribution is appreciated.

DonateDonate monthlyDonate yearly